Odile’s Notorious Magnum Opus Of Thirty-Two Fouettés

Pickle Fingers

19 January to 25 February 2023

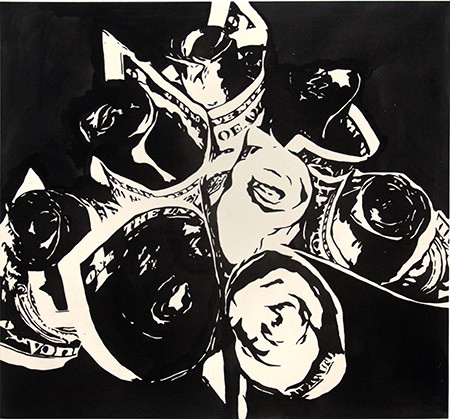

The prima ballerina in the classical ballet Swan Lake is a psychologically challenging role as the same dancer performs two very contrasting characters. The White Swan, Odette, is fragile, vulnerable, innocent and pure, and the Black Swan, Odile, is the anti-heroine who is seductive, powerful, destructive and alluring. In act III, nearing the climax of her pas de deux with Prince Siegfried, the Black Swan performs thirty-two fouettés. "Fouettés en tournant" translates to "whipped turning" and is a classical ballet movement during which the dancer turns on one foot, rising on and off of pointe while making fast outward and inward thrusts at each rotation with the other. To perform thirty-two fouettés in a row represents incredible skill, athletic prowess, technique and control. It requires strength and stamina that only comes from long dedication and commitment to ballet training. The triumph of successfully executing thirty-two fouettés exemplifies the prima ballerina's ability to perform under tremendous pressure. It showcases an ability to perform well under pressure. The transfixing turn sequence demonstrates how powerful and seductive the darkness of desires is in this dual role of Odette and Odile. After these thirty-two fouettés, Prince Siegfried chooses the Black Swan over the White Swan, compelling Odette to take her own life, and in death, she finds freedom. Yan Wen Chang's exhibition, Odile's Notorious Magnum Opus Of Thirty-Two Fouettés, investigates the relationship between a desire and a dream, their differences, and the lengths one takes to achieve them.

about Yan Wen Chang (pdf)

Yan Wen Chang works in exhibition (pdf)

FrameWork 2/23:1: Fan Wu on Yan Wen Chang (pdf)

Yan Wen Chang: Magnum Noirus in Border Crossings, issue 161 (pdf)

about Katie Bethune-Leamen (pdf)

Katie Bethune-Leamen works in exhibition (pdf)

FrameWork 2/23:2: David Court on Katie Bethune-Leamen (pdf)